The mental game

We can assume the paddlers at the Olympics are all at the peak of their fitness. We can assume they have all mastered advanced whitewater skills and technique such that there is little to choose between them. So what will make the Olympic champions?

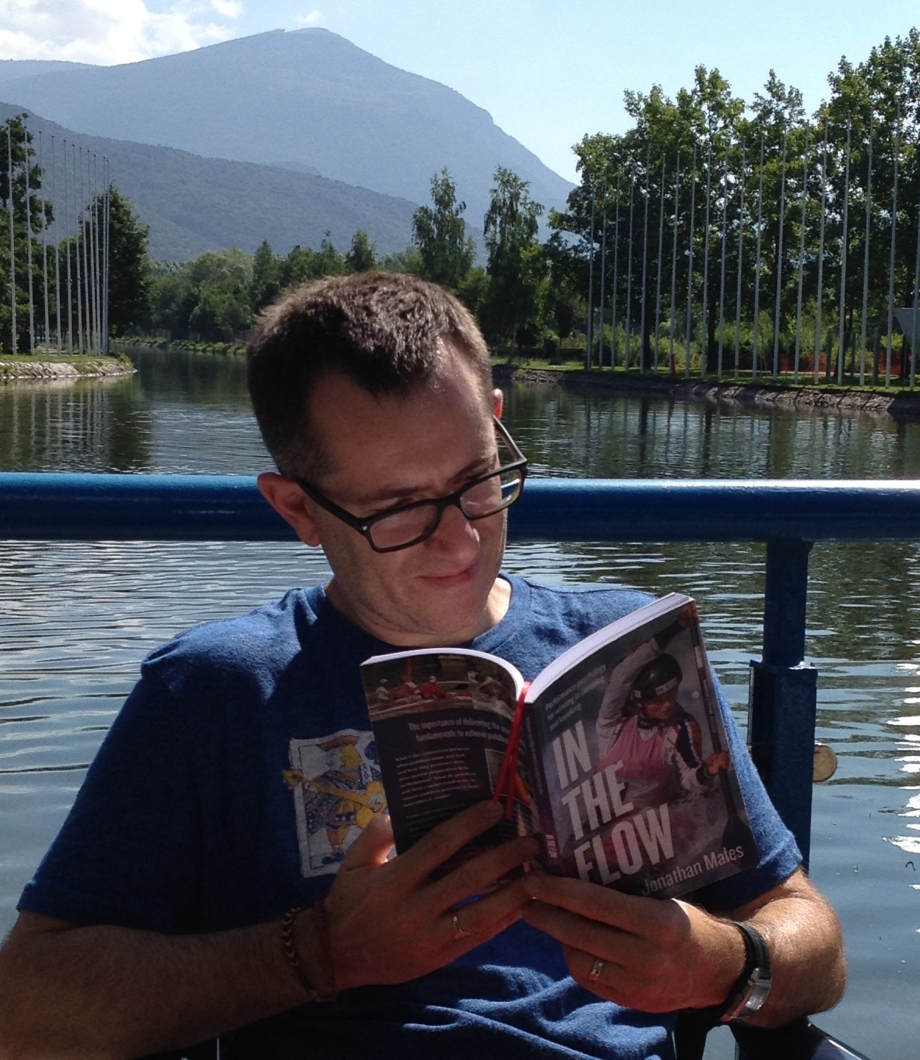

We interviewed Jonathan Males Ph.D. Males is a sports psychologist who has worked with athletes and coaches across the last seven Olympic games. He is the author of In the Flow, a book on performance psychology for paddle sports.

Males advice to the Rio athletes

“If you’re fortunate enough to have earned the right to race at the Rio Olympics, congratulations!

Only a tiny proportion of slalom or sprint athletes will ever compete at the Olympic Games. It may well represent the pinnacle of your competitive career, despite the fact that it’s harder to win a world championship where the field is so much bigger. But the chance for Olympic success comes only every four years and the media and public attention is way higher, so it can feel much more "make or break" than a World Championship.

Psychologically, the Olympics presents a combination of familiar and novel challenges. Familiar in that the essence of the event is the same as normal: for sprint paddlers, nine lanes will stretch out in front of you like they always do. For slalom paddlers, there will be about 20 gates and 300 metres of whitewater to navigate. Boil performance right down and it's just you and your boat. Stick to your tested race routine, visualize clearly, focus on your own performance, and let years of training express themselves when it counts.

If only it was so simple.

Because the Olympics become a very different competitive environment the further away from the water you are. And these differences are the ones that will de-rail inexperienced athletes and coaches.

I've already mentioned that expectations and public scrutiny are higher. There's more riding on the Olympics because the results often influence personal and national programme funding decisions. The field is smaller so the event itself doesn’t take long and can feel strangely low key, although big crowds offset this and add plenty of noise and hype. For teams that are staying in the Olympic Village there are multiple distractions to manage; whether it's the allure of the unlimited 24-hour dining hall, getting star-struck by famous athletes from other sports, or the Disneyland-like atmosphere of living in the Olympic bubble. Travel around Rio outside of accredited vehicles will be horrendous so there will be much less freedom of movement than usual. Accreditation is always an issue, making access difficult for any non-accredited support staff. Add into this the inevitable media noise about Rio being unprepared, budget over-runs, and the Zika virus, and you can see that athletes have to be well prepared for specific Olympic challenges.

The key to Olympic success is to focus on delivering your tried and tested fundamentals on the water as well as you possibly can. Do what you know works to deliver your own best performance. And at the same time, be smart about how you adapt off the water. Don’t assume that the Olympic environment will be like the world champs because it is different, so you and your coach need to be ready for these differences. Get this process right and you’ll give yourself a great chance to produce a fantastic performance. Go and enjoy it!”

Using mental imagery

The Olympic paddlers will have totally memorized the course in their heads and before they cross the start line they will already have planned down to the individual stroke. This is through the use of mental imagery. They will imagine themselves paddling every gate on the course, not dissimilar to a tennis player or golfer practicing the serve or swing in their head before they actually make it. You can either imagine yourself doing it through your own eyes, or seeing yourself doing it from above or feel you doing it (called kinaesthetic imagery), where you imagine what it will feel like to do that particular body movement and the sensation of the whitewater hitting your boat. If you watch paddlers examining the course or at the start, you will often see them with their eyes shut doing exactly this. Their bodies will often be moving as they run through this perfect mental rehearsal.

On whitewater, it doesn’t always go to plan. Here the Olympic paddlers' thousands of hour of practice come in as they adapt to a plan B until they can slot themselves back into the original mental rehearsed plan A.

Those who have competed in a prior Olympics, especially the 8 Olympic medallists are at an advantage because it will not all be new to them. The new Olympic champions will be those who can deliver The Ultimate Run according to their own mental rehearsal plan or can adapt so quickly that they do not falter from their plan. There will be top paddlers who for a split- second are pushed off their intended plan by an expected wave or a touch on a gate and will lose their focus and mental plan. They will finish but not deliver their medal winning run. One exception comes to mind; Richard Fox (GBR) hit gate one in the 1989 Savage World Championships and accelerated so much through the rest of the course he won by 5 seconds including a penalty!

Keep tuning in

In a second post today we asked Germany’s Ricarda Funk what The Ultimate Run on the Deodoro course may feel like from the perspective of the paddler.

Tomorrow’s posts will look at the role of the coach and the judge.

We welcome your interaction. Remember to use hashtag #ICFslalom across all social media. Please comment through @PlanetCanoe on Twitter